Surgeries and Procedures: Gastrostomy Tube (G-Tube)

All children need proper nutrition for healthy growth and development. But some kids have medical problems that prevent them from being able to take adequate nutrition by mouth. A gastrostomy tube (also called a G-tube) is a tube inserted through the abdomen that delivers nutrition directly to the stomach. It’s one of the ways doctors can make sure kids with trouble eating get the fluid and calories they need to grow.

Fortunately, a gastrostomy is a common procedure that takes only about 30 to 45 minutes. After spending 1 or 2 days in the hospital, children who have had a gastrostomy can get back to their normal activities, including school and play, after the incision has healed.

Still, it helps to know some of the basics so you can feel confident about what is happening during the procedure and how you can support your child once the tube is in place. The more prepared, calm, and reassuring you are about the anesthesia and surgery, the easier the experience will probably be for both of you.

About G-Tubes

Why Would a Child Need a G-Tube?

A number of conditions might cause a child to need a G-tube. Some of the most common include:

- congenital (present from birth) abnormalities of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, or intestines

- sucking and swallowing disorders, which are often related to prematurity, brain injury, developmental delay, or certain neuromuscular conditions, like severe cerebral palsy

- failure to thrive, which is a general diagnosis that refers to a child’s inability to gain weight and grow appropriately. Poor growth can be the result of an underlying medical condition such as cystic fibrosis, certain heart defects, cancer, intestinal problems, severe food allergies, or metabolic disorders, among other things.

- extreme difficulty taking medicines

- inability to burp after an operation to reduce reflux (stomach contents and acid moving backward from the stomach into the esophagus)

Several tests may be performed in the days or weeks before a G-tube is inserted. The most common is an X-ray of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) system, which allows doctors to see a portion of the digestive system.

Preparing for the Procedure

A gastrostomy requires a hospital stay, usually for 1 or 2 days.

Your child’s stomach will need to be empty on the day of the procedure. Gastrostomy in infants and children is typically performed either under general anesthesia (medication that keeps the patient in a deep sleep-like state) or deep sedation (medication that makes the patient unaware of the procedure but not as deeply sedated as general anesthesia).

These medications can suspend the body’s normal reflexes and could cause food to become inhaled into the lungs if the child vomits during the procedure. So be sure to follow your doctor’s instructions on when to have your child stop eating or drinking (for babies on breast milk only, this is typically 2 hours before the procedure; for toddlers and older children, it may be up to 8 hours before).

When you arrive at the hospital, you’ll have to fill out some paperwork and provide basic information about your child, including:

- health history

- name and phone number of doctor

- insurance provider

- any illnesses and medical conditions

- any allergies

- any medications being taken, including vitamin supplements and herbal remedies

The doctor will describe the procedure and answer any questions you might have. This is a good time to ask the gastroenterologist (gastrointestinal doctor) or surgeon to explain anything you don’t understand.

Once you feel comfortable with the information, and your questions have been fully answered, you’ll be asked to sign an informed consent form stating that you understand the procedure, the reasons to have it done, the alternatives, the risks, and give your permission for the procedure. Your child will then be given an ID bracelet and change into a hospital gown.

Starting an IV Line

A nurse will begin an intravenous line (IV) before the procedure. The skin on the hand or arm is punctured with a small needle and a tiny plastic tube is inserted into the vein. This tube is then connected by IV tubing to a bag containing a mixture of fluids and medications. The fluids flow out of the bag, into the tubing, through the tiny tube in the skin, and into the bloodstream.

Monitor Placement

A nurse will check your child’s vital signs and put in place these monitors:

- a blood pressure monitor, which is attached to a cuff that fits around the arm and periodically checks blood pressure throughout the procedure

- a pulse oximeter probe, which resembles a Band-Aid placed on your child’s fingertip and measures the level of oxygen in the blood

- a heart monitor, which uses adhesive electrodes placed on the chest to check the rhythm and rate of the heartbeat

Administering Anesthesia

Soon after, an anesthesiologist or a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) will come in to talk to you and your child. Anesthesiologists and CRNAs specialize in giving and managing anesthesia (medicines that prevent pain during the surgery). He or she will explain the details about the type of anesthesia to be used.

In addition to checking your child’s breathing and heart rate, the anesthesiologist or CRNA will ask again about your child’s medical history, particularly any family history of allergic reactions to anesthesia.

You’ll also be asked how long it’s been since your child has eaten or had anything to drink.

After you’ve provided all of this information and have had your questions answered, you’ll be asked to sign an informed consent form that authorizes the use of anesthesia.

Shortly before the procedure, your child will be given a sedative (a type of medicine that helps patients relax) through the IV.

Once your child is relaxed, the anesthesiologist or CRNA will take your child back to the operating room to administer the anesthesia. A hospital staff member will direct you to a waiting area and will notify you when the procedure is over. Usually the medications are given through the IV and gas is given through a mask that covers the mouth and nose. Often, the gas has a flavor like banana or bubblegum to make inhaling it more pleasant. Within a few minutes, your child will drift into a sleepy state.

During the Procedure

There are three methods for inserting a G-tube:

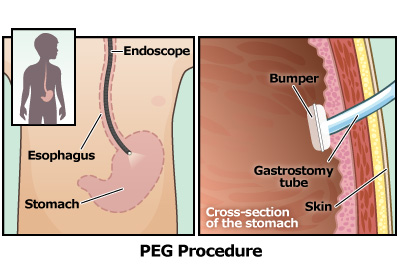

- the percutaneous (through the skin) endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)

- laparoscopic technique

- an open surgical procedure

The laparoscopic technique may be used along with the PEG approach or in conjunction with another intestinal operation performed at the same time. All methods are fairly simple and typically take about 30 to 45 minutes to perform.

PEG

The PEG procedure, which is the most common technique, uses an endoscope (a thin, flexible tube with a tiny camera and light at the tip) inserted through the mouth and into the stomach to guide the doctor’s positioning of the G-tube.

This technique may be done with the child under deep sedation. If general anesthesia is used, a device called an endotracheal tube will be used to prevent complications. This is a plastic tube inserted into the throat and the windpipe to help a patient breathe during surgery. The tube is connected to a ventilator that pushes air in and out of the lungs.

In some cases a nasogastric tube will also be used. This is a slender soft tube that’s inserted through the nose or mouth and down into the stomach to suck out stomach fluids to make sure they don’t interfere with the surgical procedure.

After the endoscope is in place, and the right location is found, a small cut is made in the skin over the stomach. A hollow needle is inserted through the cut and into the stomach. A thin wire is then passed through the needle and grabbed by a special tip on the end of the endoscope. The endoscope pulls the wire through the stomach, up the esophagus, and out through the mouth. This wire will be used as a guide to bring the G-tube into its proper position.

Next, a G-tube is attached to the wire where it exits the mouth. The wire is then pulled back out from the abdomen, which brings the G-tube down into the stomach. The G-tube is pulled until its tip comes out of the small cut in the abdomen, after which the endoscope and wire can be removed. A tiny plastic device, called a “bumper,” holds the G-tube in place inside the stomach.

Laparascopic Technique

The laparascopic technique is done by making several small incisions in the abdomen and inserting a tiny telescope that helps surgeons see the stomach and surrounding organs. The same precautions described above — the nasogastric tube and endotracheal tube — are used.

In the laparascopic technique, an incision is made in the umbilicus, or belly button, and a blunt-tipped needle is passed into the abdominal cavity. Then carbon dioxide gas is used to expand the abdominal area during the procedure so the surgeon can have a clear view of the organs.

Next, a wire is threaded through the needle and the G-tube is guided along the wire into the stomach with the help of small instruments inserted through other small incisions. Stitches and pressure from a tiny balloon are used to keep the stomach in place against the abdominal wall.

Open Surgery

Open surgery is an excellent approach for placing a gastrostomy tube, but is usually reserved for cases where the child’s anatomy won’t allow for a PEG; if there is scar tissue from a previous surgery, procedure, or illness; or if the child requires another surgical procedure at the same time.

If your child’s G-tube is being placed during surgery, the nasogastric tube and the endotracheal tube will be used to prevent complications, just as they are in the other two gastrostomy techniques. In the open surgical technique, incisions are made in the middle or on the left side of the abdomen and through the stomach. A small, hollow tube is inserted into the stomach and the stomach is stitched like a cuff around the tube. The stomach is then attached to the abdominal wall with stitches to keep it secure. A tiny balloon holds it in place within the stomach.

After the Procedure

Your child will be taken to a recovery room, sometimes called the “post-op” (post-operative) room or PACU (post-anesthesia care unit). Here, your child will continue to be closely monitored by the medical team.

The doctor will come out to talk to you and let you know how the procedure went and how your child is doing. In most cases, parents can visit their child in the recovery room – usually within 20 minutes after the procedure is completed.

It usually takes about an hour for a child to completely wake up from the anesthesia. Your child might feel groggy, confused, chilly, nauseated, scared, or even sad when waking up. That is very common and usually improves within 30 to 45 minutes.

Also, your child might feel a little bit of pain near the incision site. If so, be sure to tell the doctor because medications can be given to lessen discomfort. Antibiotics may continue for 24 to 48 hours after the procedure to prevent infection.

Your child probably will remain in the hospital for 1 to 2 days following the gastrostomy. Many hospitals allow at least one parent to stay with a child throughout the day and overnight. Much of that time will be spent learning about your child’s new G-tube.

The nurses will show you exactly how to care for your child’s tube and the skin around it, keeping it clean and infection free. You’ll also learn how to handle any potential problems, such as the tube accidentally falling out. This is important because if the tube falls out of place, the hole can begin to close.

You’ll also be taught how to give a feeding through the tube as well as what to feed. You may hear your child’s feedings referred to as “bolus” or “continuous.” Bolus feedings are larger and less frequent (more like a regular meal). Continuous feedings, which often take place overnight, are delivered by a pump to children who require smaller, slower feedings. A nutritionist will help plan a specific diet and schedule based on your child’s needs.

Some children, especially those that have had other stomach operations at the same time, may have difficulty burping or vomiting after surgery. You will also be taught to use the tube to empty the stomach of air, and occasionally liquids, as would happen when a child burps or vomits. This technique should be considered whenever a child gags or retches after the gastrostomy tube is placed.

It’s important to know that just because your child has a G-tube doesn’t necessarily mean he or she can no longer eat by mouth. Although tube feedings can be used to replace all oral feedings, in some cases the tube simply supplements what a child takes in by mouth. If your doctor decides that your child is physically able to eat, the medical team will work to encourage the skills needed for independent eating.

It’s normal to feel a little bit nervous about the tube at first, but it’s also extremely important that you feel comfortable taking care of your child’s tube, so ask plenty of questions and seek extra help if you need it.

Caring for Your Child at Home

By the time your child is ready to leave the hospital, you should have:

- detailed instructions on how to care for your child at home, including practical issues such as bathing, dressing, physical activity, giving medicines through the tube, and venting (releasing gas from) the tube

- a home health care nurse visit scheduled to make sure things are going smoothly

- follow-up visits scheduled with your doctor to check your child’s weight, as well as the placement and condition of the tube

Gastric tubes can last beyond a year before needing to be replaced. Fortunately, once the pathway is in place, replacing the G-tube is easily done by a parent or health care provider without another endoscopic or surgical procedure.

Once the site is healed, children who’ve had a gastrostomy have very few, if any, restrictions related to the tube. However, depending on the child’s age and development, he or he may be worried about how the tube looks and how others might react. If your child experiences any of these feelings, ask your doctor to put you in touch with a social worker who can help.

A feeding therapist (a speech therapist who’s specially trained in feeding issues) may also be of help. A feeding therapist can offer advice on including your child in family meals, because the social benefits of shared mealtimes are important for all kids, even those who aren’t eating in the typical way.

Changing to a Button

With either the PEG or surgical method, after a few months of healing, your doctor may recommend replacing the longer tube with a “button” — a device that is flatter and lies against the skin of the abdomen. This can be done without surgery in the doctor’s office. The button can be opened for feedings and closed in between feedings or medications. For many families, the transition to a button makes tube feedings and care easier and more convenient.

The most typical type of button is held in place with a small inflatable balloon.

Removing the Tube

If and when the doctor decides that your child is able to take in enough nutrition by mouth, the G-tube or button will be removed. Removal takes only minutes and is usually done in the office by the doctor or nurse.

Once the button or G-tube is out, a small hole will remain. It will be need to be kept clean and covered with gauze until it closes on its own. In some cases, surgery is necessary to close the hole. Either way, the scar that remains will be small.

Benefits

Gastrostomy is generally a very well tolerated, often life-saving procedure. Once the tube is in place, kids without other serious medical issues can get back to their normal activities, including school and play.

Risks and Complications

All three types of gastrostomy procedures are considered safe and effective. However, as with any surgical procedure, there are some risks, including:

Anesthesia

In some cases, anesthesia medications can cause complications in children (such as irregular heart rhythms, breathing problems, allergic reactions, and, in very rare cases, death). These complications are not common.

Bleeding

In any surgery, there’s the rare possibility of severe bleeding. However, most bleeding is easily controlled.

Allergic Reaction

It is possible that your child could have an allergic reaction to the anesthesia or other medication given during the procedure. Symptoms of an allergic reaction can range from something minor, like a skin rash, to something more serious, like dizziness, trouble breathing, or swollen lips or tongue. Allergic reactions typically develop within a few minutes after the anesthesia is given. The doctors will provide immediate medical attention if that happens.

Potential Complications at the Tube Site

The gastrostomy site itself is also prone to infection and irritation, so it must be kept clean and dry, and frequent hand washing is a must.

Symptoms of an infection can include pain; a fever of 101°F (38.3°C) or greater; and redness, swelling, or warmth around the incision. There also might be discharge that is yellow, green, or foul-smelling. If you notice any of these signs, call the doctor.

Other problems that can occur include:

- a dislodged tube

- a blocked or clogged tube

- excessive bleeding or drainage from the tube site

- severe abdominal pain

- vomiting or diarrhea

- trouble passing gas or having a bowel movement

- pink-red tissue (called granulation tissue) coming out from around the g-tube

If you notice any of these symptoms, call your doctor immediately. Fortunately, most complications can be quickly and successfully treated when discovered early.

Alternatives

By the time a doctor recommends a feeding tube, most other treatments — including feeding therapy, special formulas or diets, or medications that help to increase appetite — have already been tried without success.

And although there are other types of feeding tubes — including the nasogastric (NG) tube, which goes through the nose to the stomach, or the nasojejunal (NJ) tube, which goes through the nose to the small intestine — the G-tube is intended for long-term use. In these cases, a child’s good health and development depend on providing nutrition directly into the stomach.

When your child is having any kind of surgery, it’s understandable to be a little uneasy. But it helps to know that a gastrostomy is a brief, common procedure and complications are rare. If you have any questions or concerns, talk with your doctor.