Truncus Arteriosus

What Is Truncus Arteriosus?

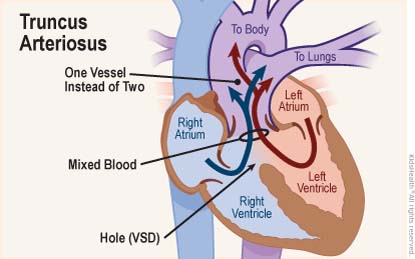

Truncus arteriosus (TRUNG-kus ar-teer-ee-OH-sus) is a heart defect that happens when a baby is born with one large artery carrying blood to the lungs and body instead of two separate arteries.

What Causes Truncus Arteriosus?

The aorta and the pulmonary artery begin as a single vessel. During normal fetal heart development, this large vessel splits to form the two arteries. If that split does not happen, the baby is born with a single common blood vessel called the truncus arteriosus.

In some children, this happens because of a genetic defect, 22q11 deletion syndrome (also called DiGeorge syndrome). In other children, it’s not yet known why it happens.

What Happens in Truncus Arteriosus?

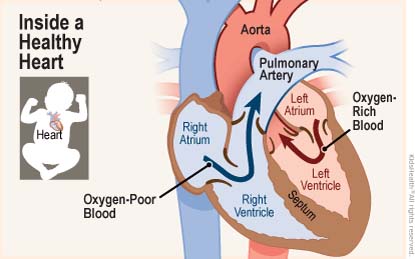

Normally, two arteries carry blood out of the heart — the pulmonary artery (which carries oxygen-poor blood from the right ventricle to the lungs) and the aorta (which carries oxygen-rich blood from the left ventricle to the rest of the body).

But in truncus arteriosus, the arteries didn’t become separate — instead, a baby’s heart has one large artery.

Almost all children with truncus arteriosus also have a ventricular septal defect (VSD) — a hole in the wall between the right ventricle and left ventricle. This hole lets oxygen-rich blood mix with oxygen-poor blood and go through the single artery to the body and the lungs. Because of this, the lungs can get too much blood flowing into them. This can lead to such problems as damage to the lungs’ blood vessels and the heart needing to pump extra hard.

The valve that sits between the heart and the large truncus artery is often abnormal as well. This valve may be leaky or tight, or even both.

What Are the Signs & Symptoms of Truncus Arteriosus?

A baby with truncus arteriosus may:

- have a blue or purple tint to the skin

- have fast or labored breathing

- have problems with feeding

- not gain weight as expected

- be very sleepy

- have increased sweating, especially while feeding

Doctors and nurses listening to the baby will usually hear a heart murmur, a whooshing sound between the lub and dub of the heart sounds.

A child born with truncus arteriosus might not look sick right away. But if the condition isn’t treated early, truncus arteriosus can quickly lead to heart failure and other life-threatening complications.

How Is Truncus Arteriosus Diagnosed?

Doctors can often diagnose truncus arteriosus before birth. A fetal echocardiogram (also called a fetal echo) is a test that uses sound waves to create a moving picture of the heart. This lets doctors see how the baby’s heart looks and works while still in the mother’s womb. Then they can plan how to treat the baby right away after birth.

If the problem wasn’t found before birth, most babies will show signs of this heart defect within the first days or weeks of life. Pulse oximetry, a simple test that measures the amount of oxygen in the bloodstream, may give the first clue that there is a heart problem. A heart ultrasound (or echocardiogram) done after birth will clearly show the truncus arteriosus.

How Is Truncus Arteriosus Treated?

Babies with truncus arteriosus need open-heart surgery to prevent problems. Most babies have this surgery in the first month of life.

During the surgery, the aorta and pulmonary artery are separated, creating a pathway for blood to travel from the right ventricle out to the lungs. The VSD and any other heart defects are repaired at the same time.

Before surgery, special medicines may be given to the infants to keep them stable and help prepare them for surgery. In some cases, more than one operation is needed.

What Else Should I Know?

If truncus arteriosus isn’t repaired by surgery, most babies won’t survive. Surgery to repair it is usually successful, and most babies recover well. However, some will need more surgeries as they grow.

Acardiac catheterization can help fix areas narrowed by scar tissue in some kids. All children with truncus arteriosus need regular visits with their doctors to help prevent any problems.

If your child has truncus arteriosus, it can feel overwhelming. But you’re not alone. The care team is there to support you and your child. Be sure to ask when you have questions.

You also can find more information and support online at: The American Heart Association.